The Breast

The proverbial two edged sword – that’s how I have come to view the breast. On the one hand, I still have a 15 year old boy’s fascination with the breast (this is a blog about the beautiful human, afterall). I love how every breast is different, not just from woman to woman, but even two breasts from the same woman. I love how breasts age – each decade adding a new feature, a new position. I love watching women struggle to find a balance between hiding their breasts and accentuating their breasts, especially in the workplace. I love surgically enhanced breasts and the au natural.

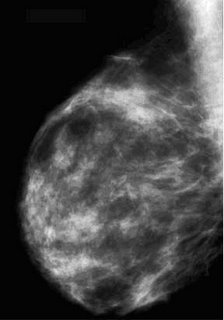

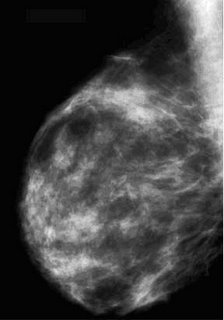

But there is a dark side, too. One in 7 women will get breast cancer in their lifetime. It’s my job to find it early and do something about it. On my exam table, there is nothing sexy or alluring. The breast is simply a body part I have to examine. Sure, I try to maintain dignity by covering the opposite breast and only exposing the portion of the breast I need to see, but these are incidentals. These women, most of whom I’ve never met, must allow me to become more intimate with their breasts then even their significant others. I look at the mammogram, and, if necessary, I set up an ultrasound. After a quick physical exam, I begin searching for any hidden abnormalities with my magic sound waves. Occasionally, I see something and breathe a huge sigh of relief. It’s an obviously benign finding like a cyst or a lymph node. Other times, it’s not so nice.

Like yesterday.

My first patient was in her 70’s. I could tell she knew it was bad even before I started the exam. Sure enough, it was an obvious cancer. We set up the biopsy and I explained to her what I saw. Her only comment was, “Please don’t tell my husband. I don’t want to ruin his Christmas.”

My second patient was not so easy. She just turned 40 and this was her first mammogram. She felt a lump, but wasn’t convinced it was anything to worry about. Even before my technologist finished hanging the films, I knew this was bad. We grade breast lesions between 1 (normal) and 5 (really, really bad). This was a 5.

Many radiologists would prefer to have someone else have “the talk.” After all, I don’t have definitive pathology to rely on. All I have are my observations and statistics. In this case, I am 98% certain that this is cancer. I’m also certain that there is no one better to give this young woman the news than me.

There are certain things we all are good at. I’m a good father and husband. I’m halfway decent on the guitar. I’m an above average poker player.

I’m an expert on giving bad news.

The key to this interaction is keeping the conversation brief without it seeming so. I strive to answer all questions without overwhelming the patient with too much information. I’m never afraid to say, “I don’t know,” or, “it’s too soon to be asking those questions.” Most of all, it’s important that I let the patient know that whatever happens, my team will be there for them. One thing I tell all patients before they leave is this:

“When you walk out that door, you will remember a ton of questions that you wanted to or forgot to ask. Don’t worry. Write them down. You belong to us now. Even if you forget everything we talked about, please know that WE haven’t forgotten. I will personally make sure that you get seen as quickly as possible so we can find out exactly what this is and what to do about it.”

It’s never easy, but the really important things never are. The good news is that I believe what I say. That patient is someone’s mom and sister and daughter. If she were my mom or sister or daughter, I’d want her seen in my hospital and I’d want her to talk to someone like me.